A Brilliant Story: The History of the Brilliant Cut | Rare Carat

In the beginning, there was the diamond crystal and man saw that it was Good. But he wanted it to be Brilliant. Thus, he made it so.

Well, almost.

Let’s cut through a couple thousand years to get us up to speed. (I promise, I’ll make this painless).

The Beginning

We shall start in the rivers of India, the first known source of diamond, when someone worked out that this stuff was pretty hard, hardest known naturally occurring mineral, in fact. It became the King of Gems. “All hail! Adamas!” They cried (meaning unconquerable or, invincible, if your ancient Greek is a little shaky). “But don’t cut the crystal, you fool, you’ll let all the magic out..." (allow several hundred years or so to pass)..."Could be a money spinner though....?” So they sold the grubbier stones to Venice.

Enter stage left a 14th century Venetian merchant: “So what the heck am I going to do with this then?" Pause. Reply: "Well we’re pretty good at cutting glass?...." There. Painless.

And that's where it began, really—the road to brilliance.

When trade routes between India and Europe were established in the 14th century, cutting centers developed across the continent. The first cities to embrace the craft of diamond cutting included Venice, Paris, Lyon, Bruges and later Antwerp.

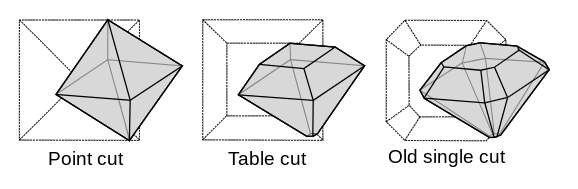

They started simply. Having worked out that diamond is the only thing that polishes diamond (going back to the hardest known naturally occurring mineral argument), they impregnated a spinning disc with diamond dust and polished up all eight sides of the octahedral crystal. Voila, the first ‘point cut’ - although to call it a cut may be a little tenuous. Perhaps just a blow dry (apologies).

Next, ladies and gentleman, we enter the age of rebirth - The Renaissance - as it rose in velvet gown and with quill at the ready, proposing notions of order and balance. Geometrical perfection was paramount - a reflection of order in the universe. Therefore, the square was all the rage. Diamond cutters wanted to stay on trend, so they lopped the top and a little of the bottom off the crystal. This is the first we see of the table facet. That flat window on the top of the stone, eagerly letting in all the light. Now, hold onto your hats, this ones called the ‘table cut’.....

Things Start Getting Serious

One thing a diamond can do is 'sparkle'. Its hardness means that it can work up such a polish that it reflects light like a mirror - referred to as an 'adamantine' luster. Not only that, it is optically dense (it slows light down a fair bit when it enters), and will split light into its spectral colors when sent in at an angle, so it will create 'fire'.

The cutters of the day were cluing into this, and as they became more and more familiar with this magnificent gem material, they were able to manipulate these qualities in the design of the cut by simply adding more facets.

The result? The 'rose cut', blossoming in the 17th century, at the latest. The rhomb and triangular shaped facets across the domed crown of the diamond worked their magic. The ones in full bloom (that’s 24 facets) were known as Dutch or Holland roses and were considered the masterpiece of the skilled cutter working out of Amsterdam. They were also a great use of a flat stone.

Just Brilliant

From here, I push open the gilded doors and sweep into the majestic halls of the court of the French king Louis XIV. He had a penchant for diamonds, which was certainly encouraged by the gem merchant, Jean Baptiste Tavernier, who brought back with him a wealth of treasures from his travels to Persia and India.

With this fascination for the gem within this French court, a fever for creation and innovation resulted.

In 1640, the table cut had its corners chipped off to create the 'taille en seige', a 16 facet diamond, and what we now refer to as the 'single cut’. But no one is ever content with single measures, now are they? What would come next was a lot more revolutionary - that is, thirty-two facets on the crown (top part of the stone) around a central table - and twenty-five on the pavilion (the lower part of the stone). The light could now bounce around the diamond and throw itself back to the eye, creating such a display when it moved, that the style of cut enchanted all that saw it. This cut became known as the brilliant. The brilliant cut. Because 'elle brille' (she shines!). Although critics of the age considered it a passing fad and were astounded by how much waste there was in the cutting. A diamond crystal could lose at best 50% yield in the creation of a brilliant.

The man (or woman....) behind the marvel remains a mystery though. It was once referenced in the early 19th century as being the work of a cutter from Venice named Vincent Peruzzi. But no information beyond that has been unearthed. Diamond historian, Herbert Tillander, found reference to a Perruzzi family in Florence, but no Vincent. There, the trail goes cold.

Regardless, he (or she...) was certainly a trendsetter. A new cut had been established that had the ability to add an extra ummph into the diamond's sparkle. (And that uumph is the uumph we still favor today.) But wait, I haven't finished yet.

Brazil

Now, venturing into the 18th century and over to Brazil, South America, then under the control of the Portuguese. There had been talk of gold, and the prospectors were scurrying across the native land in search of the treasure. On breaks between prospecting, they would play games by the river, using the stones from the bank as markers, and it turned out that a couple of the clearer pebbles polished up quite nicely....yep. They had found diamonds.

In 1759, Brazil was announced as a new source of the gemstone. More stones to play with, more fun to be had by the European diamond cutters.

The next style to, unsurprisingly, find its way onto the scene was the Brazilian Cut or 'triple cut'. It didn't differ significantly from its predecessor, except for a small flower of facets around the culet - that is, the faceted point of the pavillion.

The early brilliant or 'Perruzzi cut' also remained in circulation, as did a new 'Lisbon' cut, as the Portuguese established themselves as a centre for diamond cutting. But ultimately, they were all 'brilliant cuts', thirty-three crown facets, (star, kite- or bezel -, upper girdle and table) and twenty-five pavilion facets (pavilion main, lower girdle and culet).

At this point in history, though, the outline of the stone was still pretty much dictated by the crystal from which it was cut, so very few brilliants were particularly round. Any vague resemblance of a round shape would have to be created by carefully and painstakingly fashioning the outline of the stone with another small diamond, known as a sharp (a technique called bruting).

So these early brilliants, with their slightly square outlines, are often referred to as 'cushion cuts'.

Going South

Now it really kicks off. In December 1866 or early 1867, the date is a little unclear, 15 year old Erasmus Jacobs, the son of the new owner of the De Kalk farm in the Cape Province, south of the Orange River in South Africa, was helping out his dad on the land. Sitting under a tree to rest, he spotted an unusual looking stone. He pocketed it and took it home for his younger sister.

On visiting the house a month or two later, a keen amateur geologist noticed the girl playing with the stone and his curiosity spiked. Could that be a diamond? Not beating about the bush, it was. Just as the Brazilian prospector's pebbles had been. And the find, the 21.25 carat Eureka diamond, triggered one of the largest scale diamond rushes the world has ever known. It turned out that the deposit wasn't like Brazil or India, where the stones had been found in rivers and streams. They had found a volcanic pipe. There were hundreds of diamonds up for grabs.

From this point forward, anything coming in from Brazil and from India were called 'Old Mine' stones.

What Goes Around

So, how did this sudden in-flux of diamonds affect the terminology used to describe the cut of the stone?

Well, by the late 19th century, a D. Rodriguez patented a 'bruting machine' driven by power. No more chipping away at the corners of a diamond, one diamond could be spun against another to create a circular outline.

By the late 19th century, the circular diamond cut was the new thing. And the out-dated cushion shaped stones coming from the old mines were evidently called 'Old Mine cuts' or 'old miners'. And often as quite the derogatory remark.

Less of the Old, thanks

So, with the 58 facets and the round, bruted girdle, we are there, right? We have arrived at the modern round brilliant cut?

Nope, we now enter the territory of 'Old' Cuts.

An 'Old Cut' is a round, bruted brilliant cut stone with a small table, a high crown and a large culet. The Old Cut is, in turn, subdivided into Old European (or Dutch) and Old English, or Victorian cut. The high crown allows it to flash a lot more fire.

Maths

In 1919, still as a young man in his late teens, the budding engineer from a family of diamond cutters, Marcel Tolkowsky, calculated that if the facets on a brilliant were cut within a specific range of tolerances, the brilliance (that is the white light returning to the eye) and the fire (the dispersed light) could be maximised and the beauty of the stone increased.

The Tolkowsky Cut is the direct descendant of the modern brilliant cut. And there is a period of time between the 1920s and the 1940s when this new idea was catching up.

Diamonds cut in the Art Deco period, therefore, tend to be what is termed 'transitional' - so the table is getting a little bigger, the pavilion a little shallower and the culet a little smaller, until this little face on the bottom of the stone vanishes completely.

Beyond Brilliant

When Cut became a quality considered alongside the carat, colour and clarity of a diamond in the late 1950s, thanks to the GIA, then the proportions in the round brilliant cut became even more important - and the range of tolerances, stricter.

Today, with technology as it is, round brilliant cut diamonds can be produced with a very precise set of proportions using automated laser cutters, and for the majority of commercial, smaller stones, fewer and fewer see the hands of a human. Because of this, the Excellent Cut grade isn't desperately unachievable.

But, remember, the brilliant cut can venture beyond the round, as long as it offers up the correct anatomy - a minimum of fifty-seven facets, centred around a table, angled so as to maximise brilliance and fire. There is the heart, the oval, the marquise, the pear, the princess, the radiant, and yes, even the cushion. It is just that these days, that pillowy outline is not due to the limits of the tool, but to the choice of the cutter.

Now. That really is brilliant.

Follow Us on Social Media:

- Rare Carat on Instagram

- Rare Carat on YouTube

- Rare Carat on X

- Rare Carat on Pinterest

- Rare Carat on Linkedin

- Our Reviews

Brilliant Cut Diamond FAQs