Mother's Pride: What is a natural diamond? | Rare Carat

I'm cutting straight to the chase here.

A natural diamond is a diamond. A diamond is a mineral formed of pure carbon. A mineral is natural by definition. Mother Nature came up with the idea. She made it. Give her credit. Let it go.

But, ultimately - anyone asking the question, “what is a natural diamond" is doing so on the back of the furore surrounding laboratory-grown diamonds. Rightly. You have people like the producers of the latter, getting themselves a good slap on the wrist for marketing their stones as ‘above ground’ and ‘created diamonds’. No wonder we are getting a little confused.

It all started back in 2018, when the Federal Trade Commission decided to rock the boat and proclaim that a diamond was a diamond regardless of how it was formed - but then went on to specify that you couldn’t sell a laboratory-grown diamond as just a diamond, because the word ‘diamond’ on its own implied it was a natural diamond. Follow? Yep. ‘Neither.

Fortunately, the National Association of Jewellers and nine other leading organizations in the industry stepped in and put together a useful Diamond Terminology guideline, found here:

But, pull it down to its atomic level and natural diamonds and laboratory-grown diamonds are one and the same. They are both formed of carbon atoms crystallising in the isometric system with identical chemical, physical and optical properties. They look the same. They behave the same. They are just as hard. They are just as heavy. It’s just that one, simply put, is a man-made replica of Mother Nature’s original.

Putting it into context

Let's take a quick step back some four and a half billion years ago, to when the earth first formed from a swirling frenzy of carbon-bearing stardust. A billion years later, as our planet settled and got into the spin of things, any carbon accumulating deep enough inside the young earth, some one hundred and forty kilometres or so, crystallised as diamond. These precious little products of serendipity (ie. natural diamonds) then had a little time to kill. It would not be until they got caught up in an altogether explosive magmatic eruption that they managed to reach the surface of the earth. The ones that survived this little joyride hung around for us to find them. We did, in rivers mainly, and we soon caught on that they were pretty special - the hardest stuff we could lay our hands on - and they polished up swell, to boot.

By the time we started digging for diamonds in the late 19th century, the gem had risen even higher in our estimations and value - and it was not long before someone decided it would be quite the coup if we tried to make diamonds ourselves. Untie Mother Nature’s apron strings and go it alone.

We had worked out the required ingredient (carbon) and the method (applying high temperatures and pressures, cleverly deduced from the fact that it must be pretty hot and stuffy that deep in the earth). It was just a matter of putting it altogether. Success was finally achieved by the Swedish electrical company, ASEA, in 1953 (my straight-up favorite fact was that the first ever laboratory-grown diamond crystals were formed in the derelict outhouse of a 17th century palace in Stockholm. Seriously.) And credit where credit is due - it’s pretty impressive. Man (it was a team of men, I'm afraid ladies) made diamonds. Pure alchemy, really.

So, how is it only now that we are having this conversation? For the first fifty years of laboratory grown diamond production, (LGD’s from here on in) their primary use was in industrial abrasive applications. Because of its hardness, diamond can cut through, drill into, grind and polish pretty much anything.

The lion’s share of LGD’s are still ear-marked for toil. Think finely grooved motorways, marble countertops, or the shine on your phone screens. LGD’s have also been able to manipulate the mineral’s other properties, extending their use to heat spreaders in electrical circuits, optical windows, radiation detectors, magnetic field sensors, water purifiers, virus detectors, and surgical blades - hey, even as the odd top-end speaker tweeter. Now, that's an impressive portfolio. It is only in the last five years, however, that gem quality material has really been able to sidle onto the stage. And right now, it’s the cameo act that is stealing the limelight, and we are forgetting why we came to see the show in the first place (recap - the billion year old original. It took a fair amount of time to get her to agree to the role...)

Let’s talk technique. Just so everyone is on the same page.

LGD’s are created by two very distinct methods.

Firstly, the high pressure and high temperature or HPHT method. To be fair, this is less laboratory grown as opposed to clang-and-bellow factory grown, where the man-made crystals are born out of huge presses capable of generating pressures and temperatures akin to the depths in the earth in which natural diamonds formed. Today, hundreds of small melee gems can be grown in hours using this method.

The second, the Chemical Vapor Deposition or CVD process, is sort of like producing a diamond in a glorified microwave. Carbon and hydrogen rich gases are broken down by the microwave radiation in a vacuum chamber, teasing the carbon to settle into place on a small seed crystal (or substrate) until the layers are thick enough to form a free-standing LGD. This is a slower process, taking about a week or so to grow one carat, and generally produces a cleaner and purer crystal. It is the method favored by the major LGD gem diamond producers.

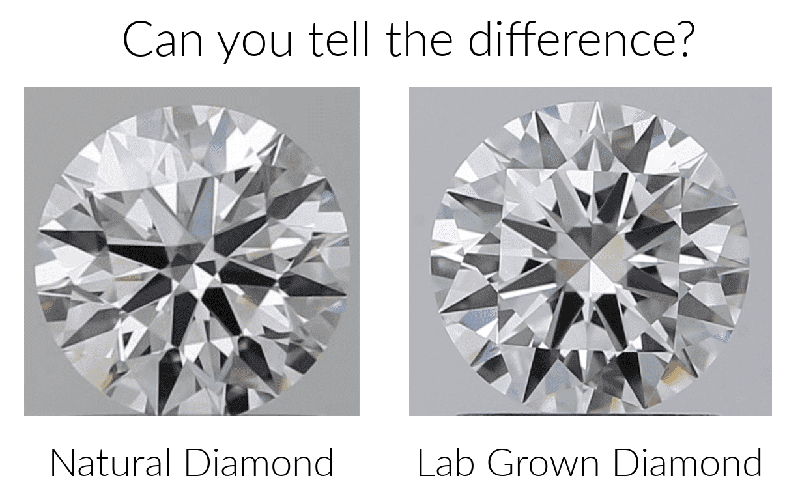

Can you spot the difference?

Honestly, no. Not really. Not over the counter, anyway. That is the point. Natural and lab grown diamonds are made of exactly the same stuff. One will seduce and sparkle with as much skill as the other.

However, because they each formed in such different ways, there are features relating to the variable growth patterns of the crystals and the impurities in each type of diamond that can be easily identified using specifically designed detection devices, available in gemological laboratories, such as the GIA.

I am ever the optimist, and hope that there are very few folk who are willing to cheat and defraud, but please do buy a diamond with an accompanying report. Whichever you are after, the GIA now offers full grading reports for both natural and laboratory grown stones. There is no getting around them.

So, why would I buy one over the other?

Cost, mainly.

LGD’s are significantly cheaper than Mother Nature’s offerings, often up to half the price for a comparable stone - so you can afford to go bigger and better for a bargain price. Why? Well, without disrespecting the exceptionally clever scientists behind it all, to grow a LGD, you set all your specs and press go.

With natural diamonds, you get what you’re given, when you get it. Gem quality natural diamonds are scarce. For that D color flawless, you’re looking at shifting one hundred thousand tones of ore before you manage to unearth a single carat of diamond.

And because of LGDs, natural diamonds are also likely to get pricier. With the lower grade, smaller natural material likely to be replaced by better quality, cheaper laboratory grown stones, it will become less and less economical to mine on large scales. The less mining, the scarcer the mineral, the higher the price.

Is an LGD a more ethical or eco-friendly alternative than a natural diamond?

This is a dangerous question with no clear answer. The laboratory grown gem diamond market is still in its infancy, really, and it is growing - quickly - so there are many unknowns.

Let's start with the ethical bit. A laboratory grown diamond manufacturer has to be cautious about proclaiming that the purchase of one of their stones is somehow preventing the plight of the poor diamond miner, when, by doing so, they are literally taking money out of those miner’s pockets. Whole economies are propped up by diamonds. Botswana, being the favored example. Kids go to school, have great healthcare, financial stability, job prospects, all on the back of natural diamonds.

Now, environmental. Yes, digging a massive hole in the ground does have a negative impact. I think the big natural diamond companies are more than aware of the problem. It's quite difficult to miss. But, conversely, both HPHT and CVD production demand a heck of a lot of energy, and for long, concentrated periods of growth time. A lot of the bigger, wealthier producers can afford to compensate for this carbon footprint. But the ever growing number of smaller producers, with their eyes on the prize, won't be. The majority of laboratory grown diamond material comes out of China, a country heavily reliant on fossil fuel for the generation of the electricity needed to grow these gems.

Overall, for such a query, I think it is best to level the playing field. Natural or laboratory grown, look at the producer before you reassure yourself that it is an ethical or environmentally positive purchase. Do not go off the nature of the material alone.

Is an LGD a fake?

Oof. No. ‘Fake’ is an ugly word. It implies that it is not real. That it is an intended deceit. That, it isn't.

I shall, instead, answer a question with a question. You are presented with two identical paintings; same subject, same size, same canvas, same paint, same style, but one is an original Claude Monet painted in 1875, and the other was painted last weekend by my incredibly gifted neighbor, $100 plus delivery. Would you call the latter a fake, or consider it a work of art in its own right? One a little kinder on the pocket - but just as pretty on the wall...

Something to think about.

Natural Diamond FAQs